Recent figures released by the major music companies are giving the industry reason for hope, though societies warn that we may not know the full extent of the pandemic’s impact for some time.

Traditionally Q4, with the run-up to Christmas, was the critical period of the year for record labels as well as publishers. This was a boom time for record sales through a combination of factors: many blockbuster releases were held back to this period; the compilations business pushed the needle into the red; gifting saw people who rarely went record shopping panic-buying and grabbing armfuls of CDs to give as presents; and magazine end-of-year polls saw an uptick in sales for those anointed as the best or most significant releases of the year.

In contrast, Q1 was quiet and a time to launch new acts; Q2 caught the early buzz of the summer festivals; and Q3, well, it sat in this strange limbo period.

This year, however, Q3 is proving to be of critical importance as a bellwether for how the music business has navigated the most difficult year of its life since Napster really started to pull the rug from under everyone’s feet in 2000. The global pandemic saw live music – and all the marketing and promotion that emendated from it – cancelled. Livestreaming did come forward to help raise money for acts and those around the business missing out on work, but it was never going to have a chance of shouldering the losses from intensive touring and a festival season that should have run from Easter to October.

This year, Q3 is proving to be of critical importance as a bellwether for how the music business has navigated the most difficult year of its life since Napster really started to pull the rug from under everyone’s feet in 2000.

The signs at the start of the pandemic were chilling. Publishers and collecting societies were warning that revenues were going to collapse as lots of the businesses they relied on for music to be played, be it live or recorded, were shuttered for most of the year (or at least large chunks of it) as different governments around the world imposed different levels of lockdown. That included touring, festivals, clubs, bars, cafes, hairdressers and more playing no music or barely any at all. And no music being played in these places meant no licensing income.

The recent numbers coming out from the major societies and publishers are, if we are being frank, a mixed bag. Plus it is all exacerbated by the fact that we are not going to get the full picture for some time.

There is much to be alarmed by; but equally there is much to take hope from. This year is going to be a ghastly one for many – and some companies will go to the wall and some writers will be forced to give up and find work elsewhere. There is no way of sugar-coating that.

To open by sounding a positive note, however, the majors overall reported an encouraging quarter (or, at least not a completely horrifying one).

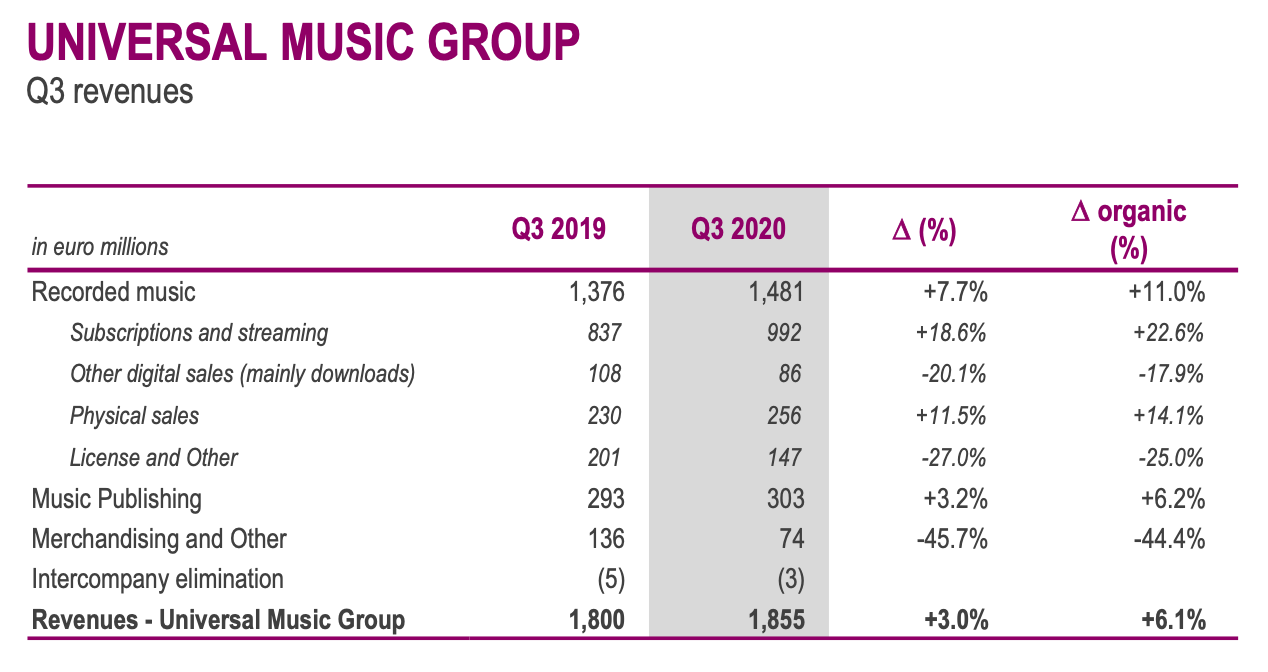

For Universal Music Group, publishing revenues were actually up in the period, growing from $293m in Q3 2019 to $303m in Q3 2020.

Source: Vivendi

“Although the COVID-19 pandemic is having a more significant impact on certain countries or businesses than others, Vivendi has been able to demonstrate resilience and adapt in order to continue to best serve and entertain its customers, while reducing costs to preserve its margins,” it said in the filing of its numbers. “Vivendi continually monitors the current and potential consequences of the crisis. It is difficult at this time to determine how it will impact its annual results. Businesses related to advertising and live performance are more affected than others. Nevertheless, the Group remains confident in the resilience of its main businesses.”

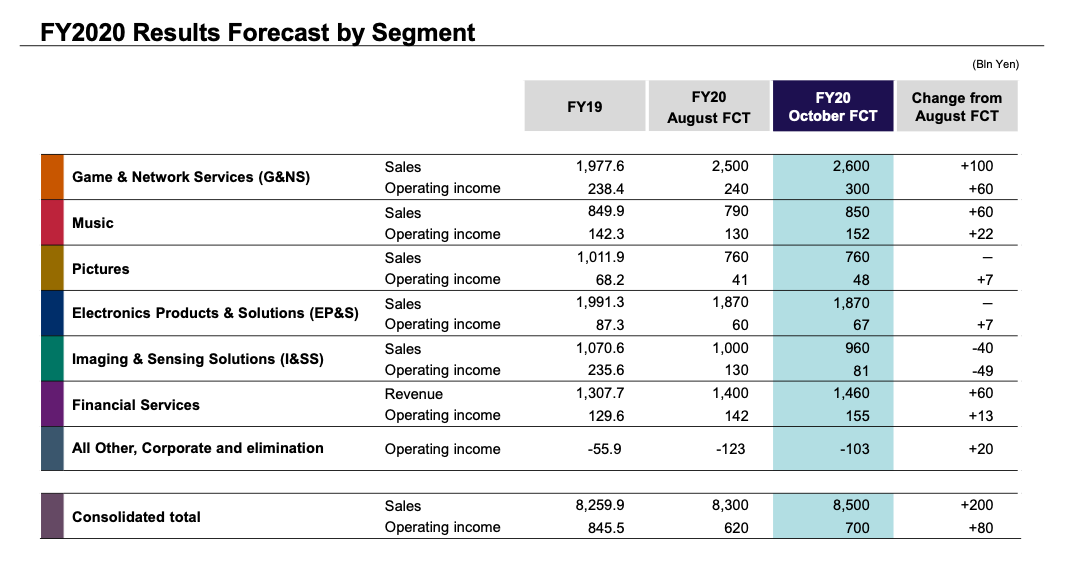

The music arm of Sony Corp (covering not just recordings and publishing but also its Visual Media & Platform division, which includes animation titles and game applications) actually increased its revenue projections and its profit projections for the 12 months ending March 2021 (when its own financial year ends). It says that part of the company is on track to make ¥850bn ($8.1bn), a growth of 7.6% from the previous financial year. This was in part down to an “expected increase in streaming revenues” from its recorded music division.

Source: Sony Corp

There was a slip in publishing income at Sony/ATV (along with Sony Music Publishing Japan) in Q3 of the calendar year, reporting revenues of $353.7m, down from $357.6m in the same period a year ago. That is a drop of barely 1% which, given the worst case scenarios being drafted in gloom earlier in the year, is so marginal as to be almost negligible. It is still just over $4m which is not to be sniffed at; but in a year when disaster was predicted across the board, it was a lot better than many dared hope.

Warner Music Group only issued preliminary numbers in October and they are for the fiscal year as a whole rather than broken into quarters, making it difficult to draw clear conclusions from. Its publishing arm reported revenues of $643m for the fiscal year ending 30 September 2019 and the company was forecasting growth for the fiscal year ending 30 September 2020. The question is by how much. At the conservative end, it is suggesting marginal growth to $645m (a mere 0.3% increase) and at the more bullish end of its projections it is suggesting that the growth could actually be to $665m (a more robust 3.4% uptick).

Elsewhere, on the CMO front, SOCAN has not published any numbers for 2020 and instead published its numbers for 2019, sitting as a reminder of more innocent – and certainly less traumatic – times. Revenues in 2019 were Can $405.6m, a jump of 8.2% from 2018.

While the major publishers have all seen (or expect to see) growth this year (or, if not, then only a marginal decline), SOCAN published a warning in June that it was expecting its international revenue to be down 10% compared to 2019’s international revenue – so around Can $365m based on what it reported later in the year for last year’s revenues. It layered on even more caution at the time, saying that 2019 “was a record year” for international revenue, meaning the drop, when it happens, will be bracing.

“Members will not experience the decline in international royalties until, at the earliest, the second half of 2020,” it said. “More likely, you will experience changes in early-to mid-2021. The time required to collect from foreign societies, transfer data and match performances is complicated and takes longer than domestic revenue to be processed, typically needing nine months to a year to complete.”

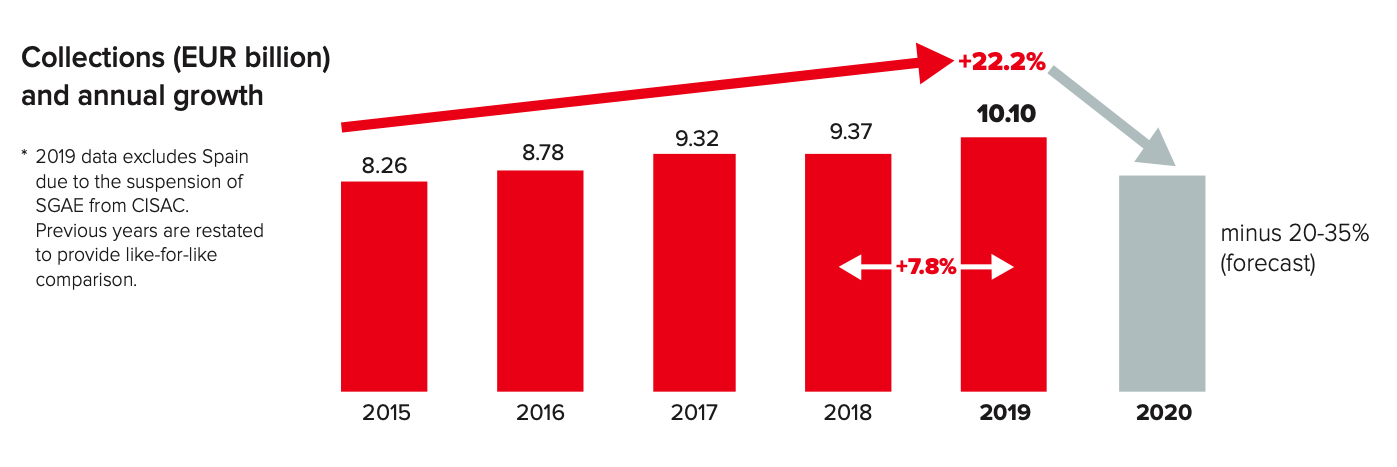

In late October, CISAC was writing the future in the blackest of ink. Its Global Collections Report was forecasting that lost music royalty collections for publishers globally this year could be, in a best case scenario, €1.8bn ($2bn) and, in a worst case scenario, €3.1bn (equal to a global revenue decline of anywhere between 20% and 35%). That is saying, at best, that the market will shrink by a fifth and, at worst, a third. It did try and balance that out by suggesting that streaming revenue could be up 15%, but that would not offset the overall losses as digital in aggregate makes up just 22.5% of global collections.

Source: CISAC Global Collections Report 2020

“This year, we have all been caught in a perfect storm,” is how Marcelo Castello Branco, board chair of CISAC, put it. “The coronavirus pandemic has thrown into reverse our global growth, and its effects will be felt throughout 2021 and 2022. This troublesome period is clearly not over – but it is fair to say we are all building bridges to whatever comes next while staying positive and alert to future opportunities and challenges. We must now battle to stay in the game and be ready to support, represent and pay our right holders what they deserve and expect from all of us”.

PRS for Music was also forecasting a major downturn in its revenues in 2020. Speaking to Music Week in August, CEO Andrea C Martin was warning the sector to expect a drop of between 15% and 25% compared to 2019 and that it would take at least until 2022 until the business saw revenues like it had last year.

In Australia, things are deeply gloomy too. The country was ravaged by bushfires at the start of the year and was then immediately hit by the pandemic. APRA AMCOS reported group revenue of Aus $474.5m for its 2019-20 financial year, a minuscule increase of just 0.6% from the previous financial year. The extra kicker here was that it was working on a budgeted figure of Aus $488.9m which it obviously fell short of. Public performance was most badly affected, slipping almost Aus $20m to Aus $73m.

The organisation was not trying to play down what it will have to report this time next year. “With restrictions remaining on live music, concerts and touring, music royalties are expected to take a more substantial hit in 2020-21,” it said.

At the heart of all of this uncertainty for societies is the way royalties come into the business. “It’s well known that publishing isn’t always the fastest-moving part of the music business,” as MBW puts it. “It can often take anywhere from six months to two years for royalties from songs licensed by the likes of broadcasters, clubs or restaurants to trickle through the system until rightsholders actually get paid.”

Indeed, Sentric told Music Week recently that it sees on average a nine-month delay between usage of music and receipt of royalties.

Is the real extent of the problem then for the major publishers not going to show up on their balance sheets next year when the revenues from this year come through? If there is a reporting delay of at least six months then the first warning signs of how bad it could be will only start to hit the publishers around about now.

There is a data lag here that makes trying to forecast your way out of a pandemic impossible. There are expectations for the way that it will go but we will probably not get the full story of the chaos of 2020 until the end of 2021.

There is a data lag here that makes trying to forecast your way out of a pandemic impossible. There are expectations for the way that it will go but we will probably not get the full story of the chaos of 2020 until the end of 2021.

In brief, we know a drop is just around the bend but no one can inform us just how steep it is going to be.

Speaking to Synchtank at the start of the summer, just as the enormity of what was happening was revealing itself in widescreen horror, Virginie Berger, founder of Paris-based agency DBTH, said, “The effects, especially on performance revenues, may not therefore be visible for a long time and will take several future distributions in order to be able to assess impact.”

While technology is not going to make up for the losses experienced this year, it can help provide a bridge for those writers most in need. Beyond the assorted grants that societies and services have pulled together in the early weeks of the pandemic, tools like Universal Music Publishing Group’s new payment portal, the PRS royalties dashboard and the Kobalt app are offering near-real-time reporting on earnings so that writers can at least prepare for things knowing what income is making its way down the payment pipeline. It will not lessen the impact of the drop in revenues but will allow writers at least to adopt the brace position.

There was growing concern that the halting of TV and film production this year was going to set a bomb under earnings for sync in 2021 and beyond. This is the delayed pain of the pandemic for the licensing business. The NME recently gathered together a list of just some of the shows and films affected and it makes for grim reading.

Most significantly, a number of major music-centric films have been delayed. The first major casualty was Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis biopic when Tom Hanks, who plays Colonel Tom Parker in the movie, tested positive for the virus and saw the entire production shut down immediately, although production re-started in June. The Aretha Franklin biopic got bumped several times and will now not be in cinemas until next summer. That said, a new Whitney Houston biopic was confirmed in August, although it will not make it to screen until 2022; but the positive point here is that studios are still investing in major music-centric films and the disruptions of 2020 are not getting in their way.

The live gap in most markets is being plugged somewhat by a brace of new specialist services, notably Driift, Maestro, Mandolin, Dice TV, DIUO and Oda – all of which allow both major acts and emerging acts to charge for shows and, by default, see songwriters make some money here. It is never going to make up for the losses to live this year; but the heavy investment – not to mention the way the public’s attitude towards livestreaming has changed – could set this up as an ancillary income stream when touring and festivals start to get back to something approaching normal – possibly as early as next summer. This could see live music return with a potential new parallel revenue stream in place.

In the early stage of the pandemic, even the most optimistic scientists were suggesting that a vaccine could be years away and that public gatherings in most countries were going to be impossible for a long time. In quick succession, however, trials for two separate vaccines have delivered results that were inconceivable even two months ago.

Of course, we must not get carried away on a wave of false optimism here as they still have to go through more testing and then there is the huge matter of vaccinating whole populations. Not to mention mutations in the virus that could make these vaccines redundant.

As Jonathan Van-Tam, England’s deputy chief medical officer, recently put it, “This to me is like a train journey — it’s wet, it’s windy, it’s horrible. And two miles down the tracks two lights appear and it’s the train and it’s a long way off and we’re at that point at the moment. That’s the efficacy result. Then we hope the train slows down safely to get into the station, that’s the safety data, and then the train stops. And at that point the doors don’t open, the guard has to make sure it’s safe to open the doors. That’s the MHRA, that’s the regulator. And when the doors open, I hope there’s not an unholy scramble for the seats.”

Back in March, the entire business was forced to confront its biggest threat in living memory – a threat that arrived with no warning and with no one able to predict when, or even if, a recovery could happen.

Things for the business were bad in 2020 (and we will start to get a fuller sense of just how bad in 2021), but things could have been a whole lot worse.

We end the year with cautious optimism. A vaccine is within touching distance. Things for the business were bad in 2020 (and we will start to get a fuller sense of just how bad in 2021), but things could have been a whole lot worse. It is not much of a positive to take away, but given the year we have been through – the lives that have been lost, the businesses that have collapsed – it is worth clinging to with all our might.