The UK parliament is currently running an inquiry into the streaming music economy, having called for evidence from across the music business. Earlier this week were the first verbal submissions, from a number of UK artists including Tom Gray (Gomez), Guy Garvey (Elbow), Ed O’Brien (Radiohead) and Nadine Shah.MPs heard impassioned but balanced submissions that shone a light on the reality of what it means to be an artist in the streaming era. Mercury Prize-nominated Shah explained that she makes so little money from streaming that she is struggling to pay her rent.

Clearly, the demise of live during the pandemic has created a uniquely difficult period for artists, but it has spotlighted that streaming on its own is not working for artists. The fact that policy makers are hearing this viewpoint (albeit later rather than sooner) suggests that change will be coming. But, while the focus is understandably on how to ‘fix’ streaming, it might be that efforts would be better placed building a complementary alternative.

Direct action

In Steve McQueen’s new film Mangrove, there is a intense scene in which Darcus Howe implores café owner and community leader Frank Crichlow that after Frank’s fruitless attempts to fix the problem via the system that direct action is the only way to change things: “self-movement – external forces acting on the organism”.

The equivalent of direct action in the commercial world is innovation – it comes from the ground up. In 2008 Spotify came up with an innovation that made the problem of the time –piracy – effectively redundant. What’s required now are new innovations that make the current streaming model look like an alternative, not the only choice – to enjoy music.

Now is the time

Now is the right time to be assessing the long-term impact of streaming. It is a mature business model and is the largest revenue driver in most of the world’s leading music markets. Whatever streaming is now, is pretty much how it is going to be. The future of what streaming can be is already here, today. Assessments must be on what the model delivers now, not some future potential.

Streaming’s current performance can be assessed as follows:

- Record labels and publishers have experienced strong revenue growth and improving margins. Their businesses have been improved

- Artists and songwriters have more people listening to their music than ever before and more creators are able to earn income than ever before

However, beyond the superstars, most do not earn a sustainable income from streaming alone and cannot see a pathway to this ever changing. This is Guy Garvey’s reference to the lack of any new (financially viable) music artists in the future.

A model for rights holders more than creators

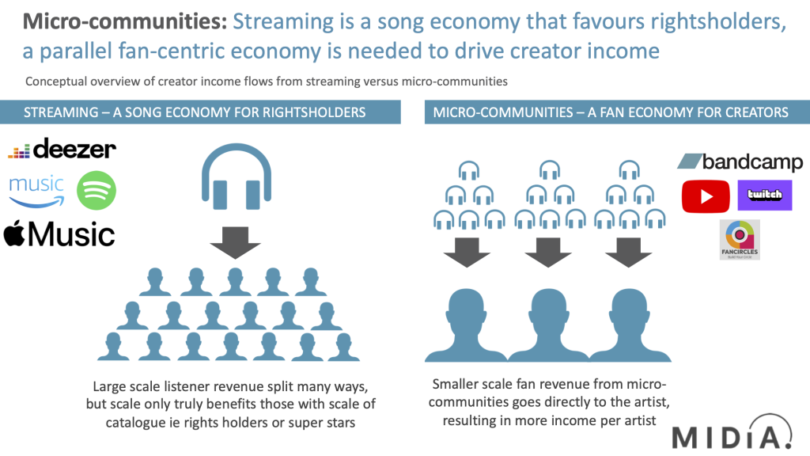

Streaming benefits rights holders more than it does creators. It is far easier to enjoy the benefits of scale if you have scale. Here is a simple illustration: if a label has 100,000 tracks played 10 times each in a month (i.e., a million streams) it will earn around £/$5,000. But a self-released artist with just 100 tracks with 10 plays each (i.e., 1,000 streams) will only earn £/$5. Though this is the product of simple arithmetic, the first amount is the foundation of a small business, the other buys you a cup of coffee.

Record labels and publishers with large catalogues benefit from scale in a way that artists and songwriters do not, unless they have a megahit – and although streaming is great for megahits, they are few and far between. Changes to licensing (and there are many ways to do that) may make things better – but they will not change the underlying dynamic; it is simply how the model is.

We have a model that works for rights holders that is fuelled by artists and songwriters. Now we need an additional, parallel, model that works for artists.

Streaming music services are incentivised to drive consumption. What we need are additional models, incentivised to drive fandom. Streaming is a song economy, and we now need a parallel fan economy.

Music used to be all about fandom. It was the way in which people identified and expressed themselves – a badge of honour and a symbol of personality. Streaming has industrialised music, turning it into a convenient utility that acts as a soundtrack to our everyday life. That may be fine, but it has simultaneously supressed those ways to express fandom. It’s not easy to express your fandom on a streaming platform, while on a social platform money must change hands.

Music fandom hasn’t died, but it just has fewer places to live.

The fan economy

So, what is a fan economy? A fan economy is one in which the value resides in the artist-fan relationship. Currently this model is pursued actively in Asia (e.g., Tencent Music in China, K-Pop in Korea) but far less so in the West. The fan economy will be defined by diversity but what its constituents will have in common is being built around micro-communities of fans.

Micro-communities that are built around an artist’s 1,000 true fans (or even fewer) allow the artist’s most loyal and dedicated fans to drive revenue that is small to the industry but large to the artist. For example, an artist with 1,000 subscribers paying $5 a month would generate the same $5,000 a month that a million streams would deliver a record label.

There are a number of platforms that are making a start, but now is the time for this to become a central music industry focus. Music rightsholders have a model that works well for them, so now they need to ensure that their artists and songwriters have models that work for them too. There is thus an onus on rights holders helping drive the fan economy, but to drive creator income rather than simply be another rights holder income.

A multi-pronged approach

This is the three-pronged approach we propose:

- Governments, support new, innovative companies building fan economy models and ensure that they provide equitable remuneration for creators

- Record labels, build teams geared at helping their artists find fan economy income streams (and take a service fee or revenue share)

- Streaming services, allow artists more real estate to showcase where fans can find other content and experiences

None of this is to say that efforts to make streaming more equitable should not be pursued; they absolutely should. However, it should be done with a clear understanding of the ‘art of the possible’. Even if rates were doubled, the self-released artist with 1,000 streams would still only earn £/$10. For an artist with a million streams a month on a big label it would change monthly income from £/$1,250 a month to £/$2,000, i.e., £/$24,000 a year. Not a sustainable annual income.

Our case is that streaming should indeed be made more equitable, but alongside proactive investment in a new generation of innovative fan economy apps. This is an opportunity to make UK Plc the innovation driver for the global music business. A unique opportunity that is there for the taking with the right strategy and support, from all vested interests.

The opportunity for the UK streaming inquiry

With the streaming inquiry, the UK government has an unprecedented opportunity to set a global standard for building a vibrant and viable future for music creators, but it is an opportunity that needs seizing now. In partnership with music creators and rightsholders, it can create a structure that supports the innovation and change the industry needs. Now that streaming has come of age, we can see both its strengths and weaknesses. Let’s use the weaknesses as a foundation for building something new, exciting and equitable. It is time to bring ways to allow music fans to express themselves and their support to artists more directly. That will keep music the uniquely valuable product it is, and not just the grease in the wheels.